Philadelphia’s yellow fever epidemic of 1793 tested the civic and religious leaders of a city trying out its role as forerunner of liberty in the new Republic. Striving printer and publisher Mathew Carey became the self-appointed narrator of the epidemic, reporting what he witnessed, remediating anecdotes, and including lists of the recently deceased in his multiple editions of A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia. Religious leaders Richard Allen and Absalom Jones offered a vitriolic retort to Carey’s depictions of the African American community. In A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People (1794), they criticized Carey for his racist depictions of African Americans’ efforts to aid the sick and the city generally in its time of great need and accounted for the many services their congregation at the Bethel AME Church had offered.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Jones and Allen’s pamphlet: scholars such as Richard Newman, Patrick Rael, and Phillip Lapsansky have deemed it the first piece of African American protest literature. It was also the first time that two former enslaved persons claimed copyright in the United States, and the authors’, Jones and Allen’s, identities are partially mediated through print. This pamphlet war then shows how battles tied to books, in both legal and cultural landscapes, refract those fought over the agency that comes with citizenship and with establishing oneself as a viable force in a international marketplace created by empire.

The yellow fever pamphlets—Carey’s, Jones and Allen’s, Dr. Benjamin Rush’s, just to name a few—have received considerable attention from scholars of the early Republic looking to understand civil, racial, and national identity in the first decade of the new nation. These pamphlets also had an international appeal, though little to no attention has been paid to the transatlantic reprints (please see my recent article in Book History on the reprinting of Carey’s pamphlet in London and Dublin). The scholarship on A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People almost entirely ignores the London reprint of their pamphlet, thereby overlooking the pamphlet as an early example of international abolitionist literature. The London publishing firm Darton and Harvey, Quakers with a bookshop on Gracechurch Street, just a few doors down from the Meeting House, reproduced A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People in the same year that it was printed in Philadelphia, and this is why I decided to create this digital edition of the London edition of the pamphlet.

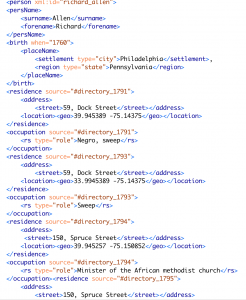

My first step was to get access to an encoded version of the Philadelphia edition. 18thConnect made this possible through Typewright; I corrected the text-version of a document that Eighteenth-Century Collections Online (ECCO) has run through its optical character recognition, but has not been checked for machine errors. After I spent a few days correcting the OCR mistakes in A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, Laura Mandell and her team at 18thConnect obtained for me the machine encoded xml file of the Philadelphia edition. Through the help of the TEI: Textual Encoding Initiative classes offered by Julia Flanders and Syd Bauman at the NEH- sponsored Women Writers’ Project and the Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI)(many thanks to 18thConnect for helping pay the tuition through its institutional partnership), I changed the encoding so that it reflected not the Philadelphia edition but the London edition. I also began to incorporate my own apparatuses. My edition then became one of the inaugural projects on TAPAS: TEI Archive, Publishing, and Access Service. In addition to offering the first digital surrogate of the London edition of this pamphlet, I have also done substantial research into who the people mentioned in the pamphlet are. Using city directories for 1791, 1793, 1794, and 1795 (I could not locate a Philadelphia directory for 1792), I have created a personography that charts what these people did and where they worked (often the same as where they lived). I then transformed that XML into a CSV, which I incorporated into CartoDB, through which I created a layered map.

sponsored Women Writers’ Project and the Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI)(many thanks to 18thConnect for helping pay the tuition through its institutional partnership), I changed the encoding so that it reflected not the Philadelphia edition but the London edition. I also began to incorporate my own apparatuses. My edition then became one of the inaugural projects on TAPAS: TEI Archive, Publishing, and Access Service. In addition to offering the first digital surrogate of the London edition of this pamphlet, I have also done substantial research into who the people mentioned in the pamphlet are. Using city directories for 1791, 1793, 1794, and 1795 (I could not locate a Philadelphia directory for 1792), I have created a personography that charts what these people did and where they worked (often the same as where they lived). I then transformed that XML into a CSV, which I incorporated into CartoDB, through which I created a layered map.

This project grew out of the research I did for my dissertation, and when I embarked on a digital edition in early 2011, I was a complete novice in using digital editing tools. My commitment to the pamphlet motivated to learn what I needed to make this digital edition a reality. My motivation would have come to naught had I not had the institutional support of 18th Connect and TEI initiatives at the Women Writers’ Project and the DHSI. I am grateful for their support throughout this project. The next phase for me is to submit the project to 18thConnect for review, and I would love any feedback before then, so please be in touch with me (mhardy@mwa.org) if you have any questions or comments on the project.